|

Some notes for a Zoom Q&A session where I was a guest of Run Tucson and The Workout Group 1. Why is adding some strength into your routine helpful for running? Strength makes more adaptable as human beings. We are constantly exposed to stressors, some good, some not so good, and improving the physical as well as mental quality of strength provides a better internal ecosystem within our body to make appropriate adaptations to those stressors…the stress of pounding the pavement the skill of making corrections on the trail, reversing the pulls of office life, the natural biological processes that occur with aging (loss of muscle, loss of tissue elasticity) counteracting the catabolic (tissue wasting) processes that accompany moderate to high volume aerobic training Historical evidence: the clusters of populations that have been successful over time have all had some basis in strength training practice. "Old school" Americans came from active lifestyle and many worked manual jobs at some point in their lives; many of the the African runners work in agriculture and have minimal access to motorized vehicles; Japanese runners enjoy very robust physical education programs in their youth 2. Are activation and stability exercises considered strength training? Yes, but for most people in the same way that mashed potatoes and asparagus fit into a meal with a steak. They’re food but they are side dishes. You can still get an adequate meal by ordering off the appetizer and sides menus and that might be all you need at the time.(Or its like a Clif Bar or gel pack aren't the same as a complete meal but in the right time and place they’re more appropriate for the situation than a giant steak.) So yes activation fits under that broad umbrella category of strength but it’s important to appreciate their proper context and limit yourself at activation exercises when you can still benefit from taking it a step further into strength training. Ultimately, activation and stabilization are prerequisites for quality movement. When we’re assessing the strength of an individual muscle, the scale runs from simply asking whether the muscle can actually activate all the way up to can it move our body against gravity and external resistance. Its all the same scale, just all part of a continuum. For a lot of things where we are highly proficient, something in the realm of activation or stability might not be an adequate load or stimulus to improve strength. But for some areas where we might be less developed or proficient, such as lateral movements, simply activating or stabilizing against a modest load might be all the stimulus you need to be challenged. But in the end its all part of the same neurological processes 3. How should someone start adding strength into their routine? Conduct a needs analysis – are you historically injured and maybe have done some strength associated with rehab but just never stuck with it? Are you historically healthy and just want make sure your bases are covered? The answers to these types of questions will help guide you to YOUR best starting point. Set up your environment for success – we’re in a unique situation right now where involving the family in a fitness routine is a very positive development, both for enjoyment and accountability Start with your running schedule and work backward from there Easy victories – Don’t have to be on some elaborate plan, especially if you’re starting from basically scratch 4. If you could pinpoint 5 strength exercises that are the most helpful for runners, what would they be?

Strive to include an exercise from each of these categories. The specific exercises will be different for everyone, but these are the key movements to focus on. The examples provided are some of my preferences, but there are many options to choose from. Pull - pull ups, rows Push - overhead pressing, push ups Hinge - single leg deadlift, glute bridge Squat - split squat, goblet squat Core - plank, Turkish getup 5. Can runners over-do it when it comes to strength training? Absolutely! But the effects are typically subtle and the effect can be be delayed for several days or weeks Biggest problem I see isn't overdoing it in an absolute sense, but in a relative sense. Most of the time when runners overdo it, the overdone program wouldn't be too much if they weren't also serious about running. Usually, the error is failing to protect quality run days from interference of lower body strength work. The magic, the essence of any training approach isn’t what we decide to do or what the coach decides to do…its what we choose to NOT do… 6. Is there anything we should stay away from? Compressing or cutting out the rest periods. Shortening the rest sounds like a good idea and feels natural for an endurance athlete.... "lets save time and be efficient" or "it really feels like I’m getting after it because my heart rate is up" or "I can't stand waiting around between exercises for a couple minutes." This thinking also drives many commercial models based on HIIT training or some form of circuit training. There can be value in these when presented a certain way, but the more we shorten the rests, the more we deviate from actual strength training. If you need more endurance, then look to your running program, don’t try to create something in the gym.

0 Comments

Here's a very simple movement assessment that I often recommend to people that you can complete on your own. This five part assessment has been around since the 1990s and is something I've used remotely with athletes for years. But with the shift of more training and treatment into the virtual space, this assessment and others like it are becoming more integral pieces of the training process. Originally appearing in Gray Cook's Athletic Body in Balance, this assessment looks at five movement patterns: an overhead deep squat, hurdle step, inline lunge, active straight leg raise and trunk rotation. You may recognize a form of these from the Functional Movement Screen. Other than some small details in execution, the main difference is these are graded on a PASS/FAIL basis. The purpose here is not to dissect movement into minute details but instead to have a way to quickly determine if someone has major gaps that we need to identify before exploring heavier loads (which can take the form of additional weight, speed or complexity). There are plenty of different ways to assess remotely, but I have found this one to seamlessly transition into the next phase of the training process. You might wonder," only five PASS/FAIL moves, how can that be of any value?" Remember this is simply a starting point that guides us to the next step, whether that is getting after it in training or doing more detailed assessments of particular results (that might otherwise be unneeded in some individuals). Bottom line: If you have an injured limb and are unable to train as normal (or train at all), training the other side can still yield benefits of the injured side Question time….Let’s say you injure your left knee. What is the best strategy for your training plan? 1 Push through pain no matter how bad it is. Don’t change your training plan. Rest is for sissies 2 Continue to train the right knee, so long as it doesn’t further injure or provoke symptoms in the left 3 Stop training both legs because you don’t want you’re right leg to become too strong relative to your left and develop an asymmetry There is a “best” answer here and that answer is number 2. Answer number 1 is ridiculous, so we’ll put that one aside. Number 3 sounds compelling and while it wouldn’t necessarily be “wrong” to go that direction, there are several reasons why number 2 is better. Again, this is all based on the caveat that the training you do for the uninjured limb doesn’t put the injured limb at further risk of injury or delay healing. For example, let’s say you were doing some single leg activities on the uninjured leg, but each impact sent a “shock” through the injured leg. Your best bet is to either find different activities or delay training the uninjured limb until it can be done safely without provoking the injured limb. In the literature, the concept of training effects on one limb being felt on the opposite side limb is called cross education. And to the surprise of some, the evidence is quite clear that cross-education works. Unfortunately, what should be the standard of care (training the rest of the body at the highest level possible in a way that supports the healing process), is instead a novel concept to many. There are several reasons why cross-limb education is not promoted more. One is that the medical process is often siloed and sees the world with tunnel vision. For example, most orthopedic surgeons are going to just look at the injury and not even consider. That’s not meant to be critical, it’s just the nature of their job. They’re good at going into a damaged body part and making structural corrections using surgical techniques. They aren’t paid to tell you how to train. Similarly, most PT’s in a “traditional” outpatient setting aren’t getting paid to consider the opposite leg (and in some cases are actively discouraged from looking anyplace other than the site of the injury…Not their fault, that’s just the nature of the system in which they work). uninjured limb.

What does the evidence say?....A meta-analysis by Green (2018) reviewed 96 studies on cross education involving healthy young adults, healthy older adults and patients, finding an average strength gain via cross education of 18% in young adults, 15% in older adults, and 29% in a patient population. Although prior meta analyses had shown conflicting results on gender differences and upper versus lower limb effects, the studies compiled by in the Green meta-analysis revealed no significant differences. Overall, the average cross body transfer ranged from 48%-77% in the compiled studies, meaning that the immobilized limb experienced strength gains of 48%-77% of the trained limb. Again, this isn’t just one study on a homogenous group of subjects…this is 96 studies in a variety of populations. (Another interesting finding was that electrically stimulation of muscles appeared to have a greater cross-education effect than voluntary stimulation). WHY cross education works remains up for debate but most evidence points to neurological mechanisms as the primary factors. Per Cirer-Sastre (2017), “this owes to the fact that no significant vascular adaptations have been found, nor were any histological changes in hypertrophy levels, in enzyme concentration, in contractile protein composition alteration, in fiber type or in cross-sectional area.” In short, strength is function of the nervous system, and the effects of nervous system output are global, meaning not specific to any single body part. Although the evidence has been relatively settled that cross-education does exist via single sided training, HOW to facilitate cross-education is less clear although a meta-analysis of ten studies by Cirer-Sastre, “to optimize contralateral strength improvements, cross-training sessions should involve fast eccentric sets with moderate volumes and rest intervals. Finally, approaching this from a pragmatic standpoint, if you sustain an injury to a limb, you could continue training the other limbs and have three “good” limbs or you could stop training both the injured and non-injured arm/leg and have two “good” limbs. Which sounds better? The concern about developing asymmetries is logical, but overall is far overblown. As we know from the research, the cross-education effect will mitigate strength losses from inactivity by an injured limb. Further, even if cross-education did not exist, you’re better off having to bring one limb up to speed rather than losing strength in both sides have having two limbs to return to normal. Simply makes no sense why you would voluntarily weaken a perfectly healthy limb. Even if an asymmetry develops during a recovery period, its not as though you were going to hop right back into peak training after you get over the injury. You might as well give yourself the highest “baseline” with a strong, healthy limb rather than let both sides regress. REFERENCES Lara A. Green & David A. Gabriel (2018) The effect of unilateral training on contralateral limb strength in young, older, and patient populations: a meta-analysis of cross education, Physical Therapy Reviews, 23:4-5, 238-249, DOI: 10.1080/10833196.2018.1499272 Cirer-Sastre R, Beltrán-Garrido JV, Corbi F. Contralateral Effects After Unilateral Strength Training: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Training Loads. J Sports Sci Med. 2017;16(2):180–186. Published 2017 Jun 1. “Girl push ups.” Such a horrible term. Thankfully, the term is not used so much anymore, giving way to the less derogatory “push ups on knees.” But terminology aside, I would argue that this form of push ups should probably be retired as well no matter what we call it.

If you want to give yourself the best opportunity to achieve one good push up or give yourself the best opportunity to do even more good push ups, then I believe there are much better methods to accomplish the goal, several if which I will cover in this post. Don’t get me wrong…If someone just wants to crank out the reps and get a good ol chest burn, then have at it! But if the goal is to achieve your maximum physical potential, manipulating other variables is a better approach. The simple reason is that taking the push up down to the knees turns it into a different movement pattern. The push up is not just a chest movement – it also involves control of everything below, and even demands mobility from the feet, ankles and hamstrings. Check this out: Here’s a group fitness member who some would label as having a “weak core” based on the picture. But would you believe her problem was actually a painful right big toe, which she is understandably hesitant to bend! When we offloaded her lower body with the band, she was able to place more weight into her legs and successfully perform a complete push up movement. Had she gone down to her knees, she would be missing out on all those positive qualities we experience from a regular push up position. One of my all-time favorite movie scenes is from Karate Kid, when after spending countless hours doing “chores” for Mr. Miyagi, Daniel complains one night that he’s been Mr. Miyagi’s “slave” and hasn’t done any karate training to prepare for the All-Valley Karate Tournament. What follows is a profound reminder that EVERYTHING he’s been doing is karate training. (and gotta love Mr. Miyagi’s on-the-spot shoulder joint manipulation haha!) So what’s the point of sharing this clip, besides an excuse for me to watch some Karate Kid? Everything we do in training has a reason. Quite often that reason connects to important aspects of our life. In athletics, each exercise helps condition the body in some way to improve sport performance. But for daily life, exercise selection can also have far reaching benefits.

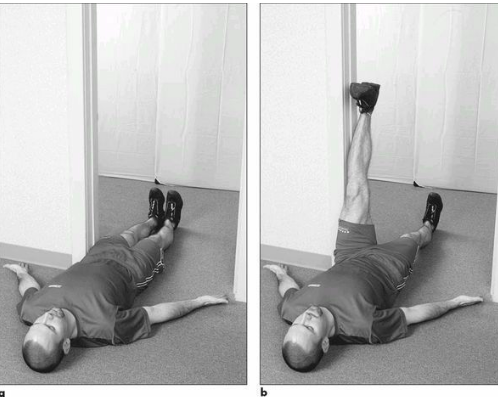

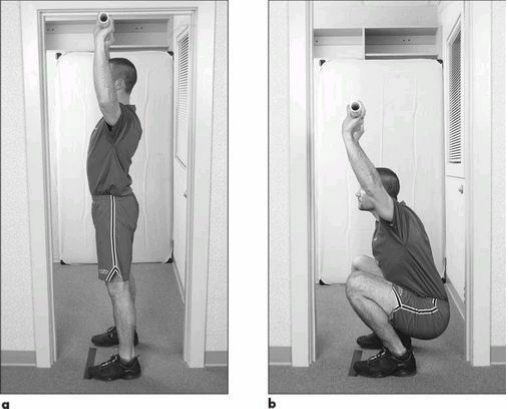

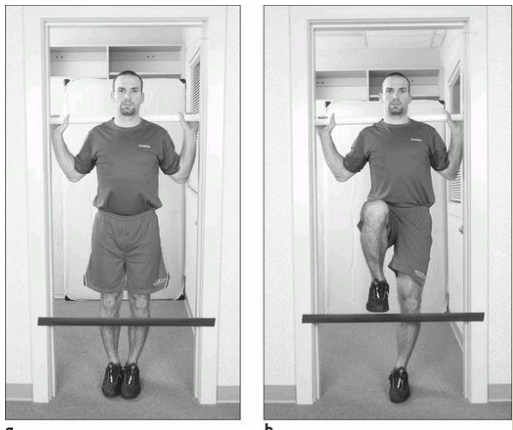

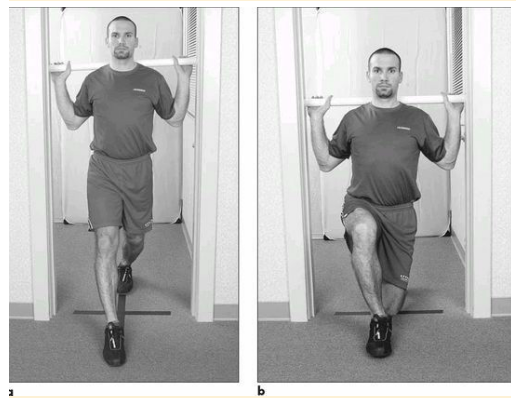

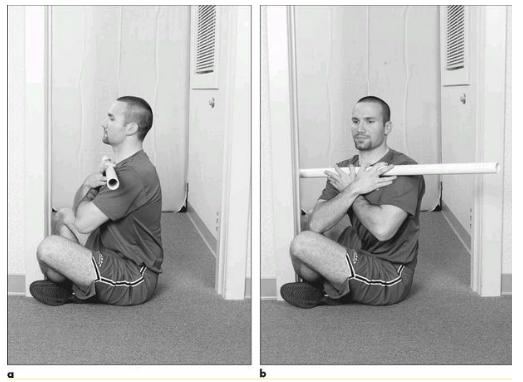

Hinge patterns are important for many reasons, but the ability to pick up objects from the ground is a practical one. Many students and patients have regained and even improved their abilities in this area simply by learning proper mechanics. We can take the hinge and turn it into a powerful conditioning exercise with kettlebell swings, or we can simply use the hinge as a teaching and rehabilitation tool. Remember, it’s not just about the exercise, it’s about what the exercise EMPOWERS you to do. Exercise can be life saving. And I do mean that literally. Falls are one of the leading cause of accidental deaths worldwide. In the United States, a high percentage of accidents occur in domestic environments that we would typically consider "safe" (as compared to developing countries where many falls result from hazardous conditions). Fortunately, especially in safe environments, falls are preventable and fall recovery is TRAINABLE. Though there is plenty of discourse about fall prevention, there is less talk about fall recovery. I'd like to work backward here and start with the recovery piece because it can also have a profound effect on the prevention piece. The first key, and perhaps most important, is a mindset shift. Conventional thinking has us believe that loss of strength, mobility and function is inevitable with aging. While certain physiological changes are undeniable, we DO have the power to mitigate the effects via intelligent and consistent physical training. Believing that you can remain strong, mobile and functional indefinitely is the foundation. It is true that "Father Time is undefeated," we don't have to let him win so quickly.... Even outside the context of falls, we should also be reminded that the ability to rise from the floor is closely linked to general health. A famous recent study in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology (de Brito 2012) found in a sample of 51-80 year olds that the ability to sit and rise from the floor was a significant predictor of all-cause mortality. In that study they used a hands-free rise as their assessment, but the general concept should apply universally. So how to we use exercise to train fall recovery? One way is through variations of the Get Up. The variation which I will cover here is the Czech/Baby Getup (named as it replicates the developmental sequence that babies follow from 2 months through 12 months). This a great way to systematically build the strength and confidence to rise from the floor. Typically, if someone struggles with the movement, there may be one or two stages that hold them back. But because we can break down the total movement into stages, that person can fast track themselves to success. To show how the Get Up can transfer meaningfully into the real-world skill of recovering from a fall, I have placed several key stages of the Get Up beside key stages of a person successfully recovering from a fall in the home (note: this was only a simulated fall demonstrated by an occupational therapist, not an actual fall. You can find the complete video here). As you look through these images, pay attention to the similarities in alignment and support, particularly how we rely on skeletal structure for foundation. I hear many people say "oh I'm not strong enough to get off the floor," but strength is rarely the primary limitation. Instead, if you know what positions to seek on the ground, the strength demands are achievable by most people. The first step above is getting yourself "organized." In the Getup we use a "90-90" position representing 3-6 months as our base. After a fall, the key is to get yourself into a position where you are prepared to move to a more advanced stage. Next we move into a position based on 5month sidelying. In the prior stage we had our entire backside for support. Now we have progressed to lateral support, though you should still have adequate stability to allow transition to the next stage... The 7 month low oblique sit is a transitional movement that begins to create separation from the ground. Instead of lying entirely on your side, you transition to low support on your bottom elbow. As noted above, this is more a test of knowing how to position yourself rather than a test of raw strength. In "real life", rather than holding a kettlebell in your top arm, you can use that arm to help prop yourself up. If you can accomplish this transition while training with a kettlebell then doing it "for real" is entirely in your ability! In the 8 month high oblique sit, we have transferred support from the elbow to a straight arm, but the overall concept is the same. Now, the left photo is actually about a half step in advance (having begun a transition into crawling), but that's mainly because her right arm is free to add support to her left arm (and she also knows her next move is to initiate crawling). The main key here is that transition from the elbow to the outstretched arm, training it in the gym with single arm support, but also knowing that you'll likely have both arms to help ina . real scenario. I've zoomed in slightly with this one because I want the focus to be on the legs, which are now organized into a forward crawling pattern on the left and a slightly advanced tripod position on the right. Without holding a weight you could certainly transition directly from sidelying into crawling, but with the weight in hand you are driven toward a more uprighting direction rather than horizontal travel as in a crawl. We are almost there! Now it is time to stand up. In a domestic environment, once you have crawled toward a piece of furniture to help prop yourself up, use your arms for support and propulsion and just stand up with your legs. The kettlebell variation involves the same pattern but without the arms to help. However, one subtle move that is key for the kettlebell Getup and that would make standing up easier at home is to flex that back foot so it can provide a little extra drive. You should be able to move to higher ground without it, but know that it is there if you are struggling. And now we're safe! One you get up to the couch at home, you can gather yourself and assess your body and call for help if you need any injuries attended to. In the gym however, we can finish off the sequence with a little overhead squat. Either way, the we've reached our objective, though in the gym we're going to reverse the move to complete the rep.

CONCLUSION Hopefully this explanation adds clarity as to WHY the Getup is such a powerful set of skills to own. Yes, there are MANY ways to teach recovering from a fall and many critical skills to help prevent a fall, but we find the Getup (especially this version) to offer a well organized teaching and treatment template. Even if this is not something you personally struggle with, chances are someone close to you may benefit from improved function in this area. Additionally, although I started this discussion with a gloomy backdrop of fatal falls, also consider the positives that can result from maintaining the ability to rise from the floor. How often do we hear people lament the inability to play with their grandkids on the floor? Too often people accept this loss of function as inevitable and permanent, which is unfortunate, because these skills can be cultivated when progressed safely. Think of all the enrichment it would add to your life and your family's life when you not only maintain your mobility but even expand it! If you need any guidance in this area, whether for personal training or physical therapy, please reach out to us here or visit us in person at GRITfit, Inc. at 7980 N. Oracle Rd.; Suite 110, in Oro Valley, Arizona. |

AuthorAllan Phillips, PT, DPT is owner of Ventana Physiotherapy Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

2951 N. Swan Rd.

Suite 101, inside Bodywork at Onyx

Tucson, Arizona 85712

Call or Text: (520) 306-8093

[email protected]

Terms of Service (here)

Privacy Policy (here)

Medical disclaimer: All information on this website is intended for instruction and informational purposes only. The authors are not responsible for any harm or injury that may result. Significant injury risk is possible if you do not follow due diligence and seek suitable professional advice about your injury. No guarantees of specific results are expressly made or implied on this website.

Privacy Policy (here)

Medical disclaimer: All information on this website is intended for instruction and informational purposes only. The authors are not responsible for any harm or injury that may result. Significant injury risk is possible if you do not follow due diligence and seek suitable professional advice about your injury. No guarantees of specific results are expressly made or implied on this website.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed